Pat Rielly was never afraid to stand up for the little guy.

Pat Rielly was never afraid to stand up for the little guy.

In 1953, the 6-foot-tall junior reserve forward on the Sharon (Pennsylvania) High basketball team was on his way to play in the state regional finals in Pittsburgh when the team stopped for dinner in Zelienople, Pennsylvania, a borough north of Pittsburgh in the heart of coal and iron country.

Rielly noticed that his three Black teammates – Charlie Shepard, Charlie Mitchell and Edward Woods – weren’t eating and sidled over to talk to them.

“I said, ‘What are guys doing? Are you saving your $5?’ ” Rielly recalled more than 60 years later. “Mitchell said, ‘They won’t serve us.’ I said, ‘Why?’ All three stared at me and said, ‘You know why.’ ”

This sort of discrimination was illegal but still prevalent, even in southwestern Pennsylvania, and it sent Rielly into a rage. He was the eighth or ninth man on the team, a sub, but he knew right from wrong. When he approached the owner and asked politely why his teammates were being refused to be served, the owner didn’t hide his contempt. “We’re not serving any (N-word),” he said.

With the courage of his convictions, Rielly said they would not pay until the entire team was fed. The owner wouldn’t budge. Neither would Rielly.

“So, we got up and left,” Rielly said. “We stopped and got something to eat another 20 miles up the road, closer to Pittsburgh.”

To Rielly, his memory of the game, which the team won, paled in comparison to the lesson he learned that day.

“You do the right thing, and sometimes you get criticized for it,” he said. “But when you do the right thing for the right reasons, it turns out the right way always.”

In the early 1960s, Rielly was traveling with a handful of fellow Marines. They needed a few more hours of flight time and convinced the pilot to fly to Reno, Nevada, the self-proclaimed “Biggest little city in the world,” where Las Vegas-style gambling, entertainment and dining is compressed into a few city blocks. As only Rielly could do, he placed a roulette bet not even understanding the rules and won several thousand dollars at a time when that was a lot of money. He took everyone to dinner and ordered a feast. After paying the bill, he still had a wad of cash left over, so he tipped the waiters generously, loaned some money to his pals and went into the kitchen. The employees stopped what they were doing to hear him speak.

“My mother was a dishwasher,” he said. “That’s why I was able to play golf on Mondays. This game has given me everything.”

Then he handed the dishwashers in the restaurant a stack of cash from his winnings. Most of them didn’t understand a word he said, but they shook his hand and gladly accepted the money.

These two dinner stories illustrate why Rielly was the right man at the right time to be serving as the 26th President of the PGA of America in 1990 when Shoal Creek Country Club in Birmingham, Alabama, was scheduled to host the PGA Championship, and professional golf would be forced to change its rules regarding clubs with exclusionary practices. This was uncharted territory for a golf association and a watershed moment in golf’s race relations. It demanded a leader with a dose of humility just below his confidence.

“His own personal integrity matched the integrity of the game he loved,” said Rielly’s longtime friend and former PGA Tour Commissioner Deane Beman.

But it wasn’t until more than 20 years later that Rielly learned just how important his role in a long-forgotten dinner played in launching an era of inclusion. Then he insisted this story wait until after he died. Now it can be told.

Dick Smith, a pro at Woodcrest Country Club in Cherry Hills, New Jersey – a predominantly Jewish club – and the man who succeeded Rielly as PGA president in 1991, also came from humble beginnings and rose to the top of his profession.

“Neither of our families had two nickels to rub together,” Smith said. “One of our favorites sayings was ‘Never forget where you come from.’ It’s part of what made Pat qualified to deal with all of that mess, if you will, all of that situation.”

To understand why Rielly’s greatest attribute was compassion, it’s necessary to understand the circumstances of his upbringing. To Rielly, golf was a game of opportunity. While his mother labored as a late-night dishwasher at Sharon Country Club, his father worked as a machinist at Westinghouse and was a boxer who once fought light-heavyweight champion Billy Conn. In 1950, Westinghouse employees were on strike and Rielly’s father wasn’t paid for a full year. No matter how bad they had it, his mother always reminded Rielly and his brother, Billy, that someone had it worse. To put food on the table, the boys shagged golf balls and progressed to caddying at the club, dropping their earnings into a brown jug.

“I made about a dollar a day, but that was a dollar more than any other 11-year-old in Sharon was making,” Rielly told the Los Angeles Times. “When I got big enough, I started to caddie, but they only made $1.25 for a round and 10 cents of that went to the caddie master.”

By age 15, he became the caddie master and a standout junior golfer, learning the vagaries of the swing through osmosis. Rielly’s 1954 Sharon High yearbook described his devotion to the game aptly: “Pat just naturally can’t resist a golf course. With his determined Irish spirit and his golfing ability, he’s sure to be a pro someday.”

Golf led Rielly to an athletic scholarship at Penn State. There were no golf scholarships at the time so Rielly, who was a triple threat on the gridiron – he ran, threw, and punted – was given a football and track scholarship. Once there, he excelled at golf and became the captain of the Nittany Lions team before graduating in 1958.

Rielly met his wife, Sue Aiken, on a blind date his freshman year in January 1955. They went bowling and Sue won. Some family members theorize that’s why he asked her out on a second date. The couple eloped in 1958 as neither set of parents approved of their union – a Catholic and a Protestant tying the knot was considered a mixed marriage at the time. It was a decision that may have helped shape his view of inclusion.

Rielly and Sue had four children who all have been or remain active in some aspect of the golf industry. After a four-year stint in the Marines, rising to captain, Rielly spent nine months as an assistant at the Circle R Ranch and Golf Club in Escondido, California, before becoming head professional at El Camino Country Club in Oceanside. After nine years there, he moved to Annandale Golf Club in Pasadena in 1972, where he worked as the head professional until retiring 30 years later.

Rielly famously told his kids, “There’s the right way, the wrong way and the Rielly way.”

“The Rielly way always entailed a little more work,” said his son, Rick, a PGA professional and director of golf at Wilshire Country Club in Los Angeles for the past 35 years. “He said, ‘You get out what you put in.’ ”

Pat instilled this belief in his employees. There are countless individuals whose lives he touched, but the story of Rob McNamara bears repeating. McNamara’s father sneaked inside the gates at Wilshire Country Club and begged Rick Rielly to give his 14-year-old son a job in the bag room. Later, Rob worked for Pat as an assistant pro long enough for McNamara to become familiar with the unforgettable way Pat would pull his glasses down to the brim of his nose and stare at him, often finishing his request with, “You got it?”

When McNamara showed an interest in working as a sports agent, Pat asked his son Mike, who worked at IMG –the sports marketing giant founded by Mark McCormack – to arrange an interview. Rielly was a good judge of talent, and McNamara got hired. Shortly after he moved to Cleveland and started at the firm that represented Arnold Palmer, Tiger Woods and Annika Sorenstam, one of the company’s top executives, Alastair Johnston, invited McNamara to his office for a get-to-know meeting.

“It took only a few minutes for Alastair to explain that in all his years Mr. McCormack had never weighed in on a hire at my level before, but after one short call with Pat that all had changed,” McNamara said. “Pat somehow managed to convince Mark, a power-broker attorney and sports-marketing pioneer, that I was the only possible candidate that could handle the job and that it would be a massive mistake for IMG to miss out on this random ex-college golfer who at 24-years-old had little to no experience.”

McNamara has gone on to become Woods’ right-hand man, with an official title of executive vice president of Tiger Woods Ventures, for more than 22 years.

“Years later at a Ryder Cup dinner, Pat ran in to Tiger and in typical Pat fashion he had a quick chat with Tiger and reminded him that I had actually worked for him first and that he was lucky he let me go all those years ago,” McNamara recounted. “Tiger told me he ran into Pat the first thing the next morning, and in retelling me the story in our car ride to the course he imitated Pat, pulled his sunglasses down and gave me the ‘You’re lucky to have him’ line staring me right in the eyes. We both laughed out loud and talked about how they don’t make people like Pat or his dad, Earl, anymore. Pat was never done, never satisfied with just helping me at one step in my life. He was going to be in your corner forever.”

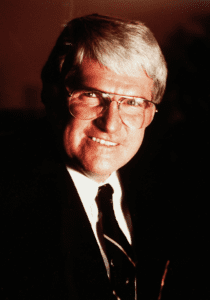

Rielly, who died May 4 of heart failure at age 87, rose to the top of his profession as president of the PGA of America in 1989. Little did he know he was about to be thrust into the center of controversy when Shoal Creek’s founder touched off a national debate with his remarks about the Alabama private club’s no-Blacks-allowed membership practices.

Hall Thompson had dreamed of building a golf course for at least 25 years. He took up golf as a Nashville teenager caddying for an older brother and kept the fever his entire life. Thompson served in the Air Force in the Pacific during World War II. In 1957, at age 34, he founded Thompson Tractor Co., which became one of the leading companies of its kind. When he was admitted to Augusta National Golf Club in 1974, his youngest daughter, Lisa, 11 at the time, shook her head.

“Well dad,” she said, “I guess this means we’re not going to build our golf course.”

That may have been the case if not for his tractor company hiring a consulting psychologist, who asked Thompson one day what unfulfilled ambition he had. He mentioned the golf course.

“He said, ‘Why don’t you do it?’ And he kept after me. He’d ask me every month,” Thompson told Southern Living magazine.

Finally, his wife, Lucy, said, “Dammit, Hall, why don’t you go ahead and build that golf course?”

Thompson did, purchasing 1,500 acres of land and hiring Jack Nicklaus to design the course with its red-brick Williamsburg Colonial clubhouse. As he put it, “We like to call Shoal Creek a Nicklaus-Thompson design.”

The course, cradled in the lap of Oak and Double Oak Mountains at the southern end of the Appalachians just 14 miles south of Birmingham, opened in 1977 and played host to the PGA Championship in 1984 and the U.S. Amateur Championship in 1986.

Thompson was a beloved local figure for his civic deeds, including annually sending half a dozen of the city’s top junior golfers to Augusta, Georgia, to watch a practice round at the Masters. In 1961 one of those guests was 14-year-old Hubert Green, who went on to win two majors during a Hall of Fame career and never forgot the gesture. The 1984 PGA Championship, won by Lee Trevino, was deemed the most financially successful PGA in history, which led to the association’s speedy return date in 1990.

In the lead-up, Thompson responded to a question from a reporter for the Birmingham Post-Herald, who asked him about the private club’s membership policy. “We don’t discriminate in every other area except Blacks,” he said, adding that he would not be told who would be a member of his club. He said the club had Italian members, Lebanese members, Jewish and female members. As for Blacks: “That’s just not done in Birmingham,” he was quoted as saying.

Thompson, who was vilified as a racist, insisted he was misquoted and apologized. However, the damage was done. IBM, Toyota and Anheuser-Busch were among the Fortune 100 companies that pulled more than $2 million in commercial advertising from ABC’s network broadcast, putting pressure on the club and the PGA of America to do something. PGA executive director Jim Awtrey, who would lose 15 pounds in a three-week period as he dealt with the biggest controversy of his career, recalled receiving a phone call alerting him early on that the PGA had a problem on its hands.

“It wasn’t a sports story,” Awtrey said. “It was a front-page story around the world.”

Birmingham was where in 1963 Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor tried to clear the streets with fire hoses and police dogs, making the city an international symbol of intolerance. Birmingham’s racial history made it uniquely suited to be the battleground for race in golf, or as Awtrey put it, “If you were going to pick the worst place in the world to have that happen, it was right there.”

In addition to a TV sponsor boycott, civil rights groups threatened to picket. No less than the Rev. Joseph Lowery threatened to bus people in from the Northeast, shut down the highways with protesters and march in front of the club’s entrance.

Lowery participated in most of the major activities of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, including leading the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 after the arrest of Rosa Parks. Lowery founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and others, serving as its vice president, later chairman of the board and from 1977 to 1997 its president. He was dubbed the “Dean of the Civil Rights Movement.” Lowery, who died in 2020, swore Barack Obama into office as the 44th President of the United States and later received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from him.

The PGA pushed Thompson to admit a Black member, but just as Rielly had experienced with the restaurant owner in Pennsylvania nearly 40 years earlier, Thompson refused to budge. Rielly recalled that members of the PGA board were willing to allow Thompson to move forward with the PGA, but he held firm and insisted they arrange contingency plans to move the championship elsewhere.

“It would’ve been a disaster,” Beman said. “Pat recognized it was the right thing to do. He was the rock.”

No decision designed to promote societal change is ever unanimous. In the succeeding days, Awtrey phoned Jack Nicklaus, outlined the situation and asked if Muirfield Village Golf Club, the private facility in Ohio owned by Nicklaus, would step in and host the tournament. Nicklaus agreed to do so, but Thompson caught wind of it and within 30 minutes Nicklaus phoned back having undergone a change of heart, saying he couldn’t host the tournament, Awtrey said.

Rielly called Beman, who offered TPC Sawgrass as a backup. In a recent interview, Awtrey said that was news to him. “I’m not sure that’s ever been discussed. That was a personal conversation between Pat and I,” Beman said in a phone interview. “We were prepared to make it happen, and we could’ve done it.”

During this tumultuous time, the PGA also contacted a New York public relations firm to help with crisis management. Vickee Jordan, daughter of Vernon Jordan, a civil rights leader and business executive who would soon rise to prominence as one of Bill Clinton’s most trusted advisers during his presidency, was employed by Burson-Marsteller public relations firm as a communications training specialist. Her job was to put Rielly through his paces with potential questions he’d face from the media. Knowing that Rielly served as head professional at a private club that hadn’t admitted a Black member, Jordan’s job was to expose any vulnerability in Rielly. She grilled Rielly hard, and Awtrey never forgot the question that broke him.

“Mr. Rielly, have you ever heard of the Emancipation Proclamation?” she asked.

Rielly, who overcame a childhood stutter, stammered. He was clearly flummoxed.

“He was right on the edge of hyperventilating,” Awtrey remembered. “We stopped right there, and it was settled: I was chosen to handle the interviews with the press.”

But Rielly took the lead on pressing Thompson to see the importance of admitting a Black member immediately.

“Shoal Creek was easy for me,” Rielly said. “I knew what I was going to do. If they didn’t do what they did, we weren’t going to be there. The game is bigger than the PGA Championship. The game is everything.”

How close was the PGA to moving its championship? Very close. “Hall didn’t think we’d move it,” Rielly remembered. “He asked my secretary (Gary Schaal), ‘How serious is Pat Rielly?’ He answered, ‘Pat Rielly is as serious as cardiac arrest.’ There was dead silence.”

Nine days before the PGA Championship, the club agreed to extend an honorary membership to Louis J. Willie, a 66-year-old World War II veteran and Black businessman who headed the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company, Alabama’s largest Black-owned employer. Willie had barely played golf in the past 20 years, but that was of little concern. He and his wife received a standing ovation when they walked into the club for a dinner that week, and it diffused the situation with the SCLC.